A Eulogy for Dawson, New Mexico Where Greek Miners Worked and Died

A EULOGY FOR DAWSON, NEW MEXICO

WHERE GREEK MINERS WORKED AND DIED

Published in The National Herald, March 18-24, 2017 Issue

Authored by Steve Frangos

TNH Staff Writer

------------------------------

We are excited to announce that The National Herald has given Hellenic Genealogy Geek the right to reprint articles that may be of interest to our group.

------------------------------

-----------------------

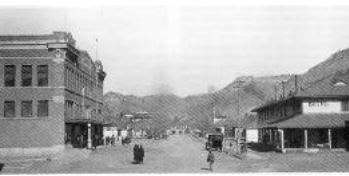

Rubble is all that marks what

was once Dawson, NM. As such,

there is too little there to even

call it a “ghost town.” Yet, what

does remain aside from the odd

mound of debris is the town's

cemetery, known both as Dawson

Cemetery and Evergreen

Cemetery.

Two terrible events led to the

cemetery, not the town, being

listed in 1992 on the National

Register of Historical Places. Today,

the Dawson Cemetery can

be found at (approximately)

four miles Northwest of junction

US 64 and Dawson Road. The

Dawson Cemetery is as much a

part of Greek-American history

as it is American labor movement

or the history of New Mexico.

By 1869, coal had been discovered

on the land that would

become Dawson. After a series

of owners, the Phelps-Dodge

Corporation (PD) bought the

area’s mines in 1906. To its

credit, PD spared no expense in

their efforts to make Dawson a

model mining community. In

time “the company built spacious

homes for its miners, supplied

with water from the company's

water system. They also

built a four-story brick building

which housed PD’s Mercantile

Department Store, which sold

virtually anything the townfolk

might need: food, clothing,

shoes, hardware, furniture,

drugs, jewelry, baked goods and

ice from its own plant.

A modern hospital was built

which maintained a staff of five

doctors and was complete with

a laboratory, surgery, and X-ray

equipment. For leisure, the miners

enjoyed the use of the company-built

movie theater, swimming

pool, bowling alley,

baseball park, pool hall, golf course, lodge hall, and even an

opera house. PD also supported

two churches, one Catholic and

one Protestant. Children attended

either the Central Elementary

School in Downtown

Dawson or the Douglas Elementary

School on Captain Hill. A

large high school building was

built that eventually employed

40 teachers, and their athletic

teams won many state championships.

The company also built

a steam-powered electric plant,

which powered not only Dawson,

but also the nearby towns

of Walsenburg, Colorado, and

Raton. Providing good-paying

jobs for the residents, the extra

features of the company town

helped keep the employment

stable, and under the new management

Dawson's population

grew quickly to 3,500 (legendsofamerica.com).”

All seemed

well and the town grew into approximately

9,000 residents

supporting ten coal mines.

Then, on October 22, 1913,

an incorrectly set dynamite

charge resulted in an enormous

explosion in Stag Canon Mine

No. 2 that set a tongue of fire

one hundred feet out of the tunnel

mouth. It was later determined

that the explosion was

caused by a dynamite charge set

off while the mine was in general operation, igniting coal dust

in the mine. This was in violation

of mining safety laws. Rescue

efforts were well-organized

and exhaustive, but only a few

miners could be rescued. Two

hundred and sixty three died in

the second-worst mining disaster

in American history. Only the

December 6, 1907, Monongah

Mining disaster was worse. In

that underground explosion,

362 workers were killed in a in

a Monongah, WV mine.

Of the Dawson 1913 catastrophe

worker casualties tolled,

146 were Italians, 35 Greeks,

and two rescuers. Despite the

fact that they were specially

equipped 'helmet-men' outfitted

with airtanks during their rescue

effort James Lurdi and William

Poisa inexplicably died. The 35

identified dead Greek miners

were: Amargiotu, John; Anastasakis,

John; Andres, John; Andres,

Pavlo; Andrios, Thelfno;

Anezakis, Milos; Anezakis,

Stilen; Arkotas, Nick; Bouzakis,

Nick; Castenagus, Magus;

Colonintres, John; Cotrules,

George; Cotrules, Mak; Fanarakis,

Michael; Gelas, George;

Iconome, Demetrius; Katis,

Gust; Ladis, Vassilias; Lopakis,

Magus; Magglis, Vassos; Makris,

Cost; Makris, George; Michelei,

Agostino; Mifinigan, Tones;

Minotatis, Emm; Nicolocci,

Nick; Papas, Cost; Papas, Nakis;

Papas, Strat; Paperi, Mike;

Parashas, Manon; Pino, Kros;

Sexot, John; Stavakis, Polikronis

and Vidalakis, Antonios

(https://familysearch.org). The

Phelps-Dodge Corporation paid

for all funeral costs for all the

victims. In addition the company

gave each widow $1,000

dead benefit and $200 to each

child.

Given the technological advancements

of the 1913-era a

Pathe newsreel of the Dawson

disaster toured the nation. A 17-

minute silent film held by the

Prelinger Archives on the Dawson

disaster can be seen on

YouTube. It is difficult to assess

the Prelinger footage, since it

seems to be the victim of an array

of editorial cuttings. Sources

suggest that this newsreel may

in fact be a reenactment. It

seems likely, then, that the helmeted

mine rescue units, seen

so prominently in this newsreel,

arrived several days after the actual

disaster (Salt Lake Tribune

October 25, 1913).

Then, on February 8, 1923,

yet another explosive disaster

struck the Dawson mines in

which 123 men died. At the

time of that disaster, women

who had run in 1913 to the

mines to see about their husbands’

safety in 1923 ran to

learn of their sons’ safety. From

1880 to 1910, mine accidents

claimed thousands of fatalities

all across the United States. Annual

mining deaths had numbered

more than 1,000 a year,

during the early part of the 20th

century. In addition to deaths,

many thousands more miners

were injured (an average of

21,351 injuries per year between

1991 and 1999). For the

1923 The Dawson Cemetery Inscriptions

and Other Vital

Records I can only find the following

Greek individuals identified

Nick Arvas; Evangelos P.

Chiboukis, Evangelos P.;

Scopelitis, Criss; Scopelitis; and

Paul Stamos among the dead

(chuckspeed.com/Dawson_Association/Dawson_Cemetery.pdf

).

As anyone visiting can see,

prominent in the center of the

Dawson Cemetery is a large section

of white trefoil crosses composed

solely of the collective

graves of miners killed both in

1913 and 1923. With so many

miners coming from other countries,

these tragedies were truly

international incidents. In

recognition of the importance

of this overall site, the cemetery

has been placed on the National

Register of Historic Places.

In 2013, Greeks in New Mexico observed the “100 Year Anniversary

Day of Remembrance”

for all who perished in the mine

explosions in Dawson. A coalition

from Albuquerque St

George Greek Orthodox Church

and St Elias the Prophet of

Santa Fe held memorial services

first at the individual churches

and then graveside services at

the Dawson Cemetery. GreekAmerican

event organizers such

as Georgia Maryol and Nicolette

Psyllas-Panagopoulos sought to

alert the general New Mexican

public about this day of observance

to much success. Other

events included the October

20th commemorative observance

at the Raton Museum

shared by historians and miner's

descendants.

Then, in 2014, the YouTube

video “The Dawson Mines – 100

Years” was aired. The focus of

that documentary is on the six

Greek miners who died in the

tragedy who were all from the

village of Volada on the island

of Karpathos: Vasilios Manglis,

Polihronis Stavrakis, Alex Kritikos,

Costas Makris, George

Makris, Vasilios Ladis. Ladis had

arrived in Dawson only two

weeks before the 1913 disaster.

This film was produced for the

Pan-Karpathian Foundation's

2014 annual 'Mnimosino'

memorial service.

Clearly, the Dawson Cemetery

is a part of Greek-American

history as well as the American

labor movement. Therefore, the

Dawson Cemetery historical

marker must be added to the

ever growing list of GreekAmerican

monuments and historic

sites.

It is exactly in this manner

that we are collectively creating

a Greek-American Historical

Commons, one location, one

person, one event at a time

Comments

Post a Comment